MT in official files for 1994

Newly-released British government files for 1994 include some fascinating glimpses of MT in the first years after her fall from power, as seen by wary eyes at John Major's No.10.

She was playing many roles at this point. There was the globetrotting icon of the right, meeting with Bush and Mitterrand, Gorbachev and the Chinese leadership, a woman still courted by her peers. There was the familiar and powerful voice of conscience, a latter-day Gladstone flaying Western policy over Bosnia. And there was her increasingly troublesome presence closer to home, particularly over Europe. This was the role that most concerned No.10.

1991-92: Troublemaker at Large

The British Ambassador's letter to London

The file opens with a telegram from New York by Sir David Hannay, Britain's Ambassador to the UN, telling of MT's meeting with UN Secretary-General, Perez De Cuellar on 8 April 1991, barely four months after she left No.10. Truly this was a "courtesy call": there is a strong sense of emptiness in this record of largely inconsequential chat. How far she had fallen, and how steeply. In office MT went into high-level meetings as well or better briefed than anyone else, with five or six points to get across and two or three things she wanted to take away. Evidently, obviously, that was no longer the case, so it is no surprise to find the conversation struggling a little. It cannot have helped that Hannay felt obliged to voice from time to time the views of the British Government, implicitly distinguishing them from hers. He was surely within his rights to do that, but MT won't have liked it. Notes later in the file show that British Ambassadors were not automatically invited by her into her meetings with world leaders. Nor were British government lodgings taken up for every visit, even when they were on offer. She quickly learned to maintain a certain distance from the official machine. The year after she left No.10 was one of the lowest points of her life and in this bleak telegram, one glimpses it.

She was happier visiting the USSR the following month where her hosts laid on a programme of meetings, speeches and visits similar to the kind she might have expected had she still been at No.10. Two and a half hours of conversation with Gorbachev was followed by dinner at his private dacha. She made a speech to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR - history's wheel really had turned a fair distance since she had proudly claimed the Iron Lady tag in her red chiffon evening gown - and met the Defence Minister, Marshal Yazov, only four months before he joined the coup against Gorbachev. There was a meeting with the Soviet PM, a big TV interview, a glitzy political dinner, a call on the Mayor of Moscow (the somewhat shambolic Friedmanite, Gavril Popov, whom she much liked), a trip to Leningrad (as it was to be for a few more months). There were also the traditional balancing items, registering her areas of sharpest disagreement with the Soviet regime - a meeting with Jewish activists and deputies from the Baltic States, as well as a dinner attended by Yeltsin's then close ally, Ruslan Khasbulatov. Yeltsin himself she did not see. He was busy running for the Presidency of the Russian Federation, the post he won the following month. She did not regard him as a shoo-in.

To what purpose was all this largesse? Gorbachev certainly had his reasons for laying on a quasi-state visit, quite apart from any sentimental response to MT's fall. He wanted Western financial support and to ease off what he saw as persisting Cold War attitudes in Washington. He also sent a rather chilling message about the Baltic States. Given a read-out of the talks by MT's long-standing translator, Manchester University Professor Richard Pollock, the British Ambassador reported to London a blunt exchange. MT told Gorbachev that she hoped the Balts would win their independence, to which he replied in the emphatic language of realpolitik that the USSR needed access to the sea and that the independence of the Baltic States was a recent thing, really no more than a historical anomaly.

Yet MT delivered for Gorbachev in one respect: she publicly called for the Soviets to be invited, as observers, to the upcoming London G7 summit, a key forum for the concerting of Western policy towards the Soviets. If more aid was to be given, this would be the place, although one should note that she balanced that support the following month in a speech to the Council on Foreign Relations in Chicago, calling for the extension of NATO eastwards.

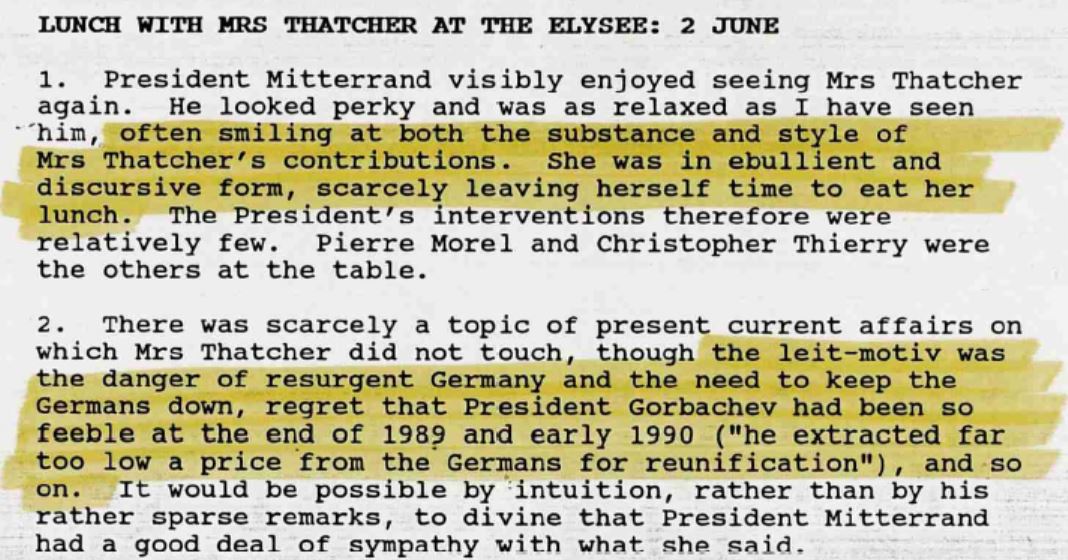

There were fewer such obvious pay-offs to the host from her meetings with other heads of government, although the records in this file suggest they went well beyond courtesy in most cases. When Mitterrand gave her lunch at the Élysée in June 1992 there was plainly goodwill and fellow feeling, indeed a meaningful continuation in some respects of what had gone before. The Ambassador's note described the President with the word 'perky', "as relaxed as I have seen him", MT "ebullient and discursive" - which is to say perhaps also perky and relaxed. They enjoyed each other's company on occasions like this. One can only smile to read that she sounded off about Germany, while he encouraged the performance without giving any hostages: "It would be possible by intuition, rather than by his rather sparse remarks, to divine that President Mitterrand had a good deal of sympathy with what she said". Plus ça change ... She had a bond with Mitterrand all the more precious to her as her own time in office receded while he remained in power. Her last meeting with him was some years away, but the emotion she showed describing it on her return is memorable - the dying President, grand and gracious, but also so vulnerable, so near to earth. Perhaps a note of that meeting will also surface.

John Major was shown the account of the Mitterrand conversation and noted: "V. interesting - a good read". So it was, but how much she would have disliked the thought of his reading it.

The file is silent on her first major overseas visit after leaving office in March 1991, when she traveled to Washington to receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Bush in a ceremony at the White House. But there is a later note of her White House visit in September 1992, just after Britain crashed out of the ERM, when MT was invited to meet Vice-President Quayle, Bush subsequently calling her into the Oval Office for a "brief conversation", a marked downgrading of status by previous standards, and far less than she got from Mitterrand or Gorbachev. The telling thing in the record is that when MT told the President that she "thought [the] Maastricht [Treaty] was dead and certainly hoped it was", the President gave our Ambassador "a large wink, apparently unnoticed by his visitor, but otherwise did not comment". Bush's re-election campaign was also a topic, his defeat by Clinton by no means unanticipated even in the White House. Strikingly, she warned him against taking a position on abortion, the President replying somewhat evasively that the issue was not as important as people supposed. It was a curious exchange, and one she often quoted in later years.

Finally, there is material on China and Hong Kong, which she visited in September 1991. Visits from departed Western leaders were a notable feature of Chinese diplomacy, of course: MT was rather obviously treading in the path of Nixon and Heath, who paid many visits to the People's Republic. But she was a less obliging guest perhaps. She pointedly asked to see Zhao Ziyang, the former Communist Party General Secretary purged after Tiananmen, held for the rest of his life under house arrest. This was "not possible", she was told. She taxed her hosts about human rights, economic reform and Hong Kong, among other things and there were "some animated exchanges". The British Ambassador was not invited to any of the meetings, so he could not be more specific than that. In truth, her position on China had evolved markedly since Tiananmen, making her a natural ally when Chris Patten became Governor of Hong Kong the following year and announced democratic reforms which brought a rift with China.

Nov-Dec 1991: The Road to Maastricht

From the British Government's point of view in the early 1990s foreign policy was almost light relief by the standards of issues closer to home. MT could circle the globe as many times as she wanted encouraging the like-minded, telling off the unholy and supping with the international great and good, if only she would steer clear of the ERM and Europe. These tangled, toxic issues had ended her premiership and began to seem as if they might do the same for her successor.

Of course, it was never remotely possible MT would simply leave well alone. The issues were too important in themselves, and the history too fraught. One can trace, though, a degree of holding back on her side in the period before the April 1992 General Election, when first the Gulf War and then the imminence of a British poll exerted powerful pressure against public dissent. The file reveals these contrary forces in play during the preparation of MT's final speech to the House of Commons, delivered from the unfamiliar territory of the backbenches on 20 Nov 1991. John Major's Press Secretary, Gus O'Donnell, sent his boss an account of a phone call he had received early that morning from Charles Powell, who had left the civil service earlier in the year but remained No.10's best connection to MT. Powell had drafted a text for her, but she had rejected it - something she rarely if ever did in their days together at No.10. He had in turn managed to persuade her to drop an alternative draft, in favour of one that he summarised in some detail for O'Donnell and described as "not too bad". Its significance lay in MT saying for the first time in public that if the principal British parties signed up to a single currency, the decision should be subject to a referendum. Although Powell thought the draft might yet be shifted in a more hostile direction by "Messrs [Neil] Hamilton, [Bill] Cash and Tebbit", the speech as delivered was close to the lines predicted. Helpfully it opened with words of support for Major in the upcoming negotiations at Maastricht, a position she continued to adopt in public when the Treaty was agreed. Major had done 'brilliantly', she said.

Jul-Aug 1992: Bosnia

In a sense Bosnia belongs under the same heading as Maastricht, because at the beginning of the break-up of Yugoslavia in 1991, some in the European Community aggressively made it a European issue. They saw an opportunity to resolve the issue speedily and so demonstrate that the Community had come of age in international diplomacy. Jacques Poos, Foreign Minister of tiny Luxembourg and rotating chair of the Foreign Affairs Council, grandly declared in words that were hung around his neck forever more:

This is the hour of Europe - not the hour of the Americans …. If one problem can be solved by the Europeans, it is the Yugoslav problem. This is a European country and it is not up to the Americans. It is not up to anyone else.

MT often quoted these words, as a sort of challenge. If this was "the hour of Europe", then how was 'Europe' performing in its own backyard? As civil war, ethnic cleansing and outright massacre unfolded across territory best known to many Europeans as a cheap (and peaceful) holiday destination, MT's focus on the topic grew stronger and stronger. She was the first figure of any stature to call for international recognition of Croatian independence, in December 1991, and as the Serbian offensive against the Croats ended, she awaited what seemed certain to follow, a Serbian war against Bosnia.

It duly came in summer 1992. The file on "Ex Prime Ministers" now released gives us the separate letters she wrote to the Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary on this topic on 30 July. These are angry, agitated letters, which must have been acutely uncomfortable to receive. Hurd was particularly hard hit: she was barely even polite, demanding towards the end not to receive "a brush-off letter" in response. To the Prime Minister she was more respectful, but in writing to him at all she was expressing certainty that the Foreign Office would deliver nothing. She talked of being 'distraught' about the situation in Bosnia and Croatia. She mentioned helping Miloska Nott, the Slovenian wife of John Nott, Defence Secretary during the Falklands, to establish a British camp for refugees, though she reminded the PM "that is not a solution. These people want to live peacefully in their own land".

Angry as these letters are, among the angriest she ever wrote, reproach is not the only emotion registered. She certainly felt that for the authors of British policy, but she was voicing also shame, because finally all those who stood aside shared in the guilt. "Freedom is selfish", a Hungarian woman had told her in 1956 when the West looked on as the Soviets crushed the reformist government of Imre Nagy. MT had rejected the idea at the time, because the nuclear standoff explained Western forbearance, but in 1992 as she told Hurd, her verdict was different.

After writing the letters she flew to Gstaad to work on her memoirs. While she was there, ITN scooped the world in reporting Serb concentration camps for its prisoners, pictures of gaunt men behind barbed wire dominating the bulletins. MT responded by publicly demanding Western action, particularly targeting the US where the Bush-Clinton presidential campaign was under way. She wrote an article for the New York Times ("Stop the Excuses. Help Bosnia Now") demanding that the West force Serbia to abandon its intervention by an ultimatum enforced with air strikes and gave a tv interview from her hotel suite to CNN. She also received a visit from the Vice-President of Bosnia, Ejup Ganic, who came directly from the besieged capital, Sarajevo. A light tea was laid out for them both and Ganic gobbled everything in sight. Eloquent as he was, his obvious hunger made the case for intervention every bit as effectively as his words.

Further papers released in July show the government preparing its response. Major and Hurd met to discuss the letters the day they were sent and military advice was sought. When it came, four days later, it was decisively against intervention with ground forces. Ministers were told it would require 16 divisions and 3 carrier battle groups, resources far beyond those available to the UK and a stretch even for NATO. Nor was there any appetite in the US Administration for such a deployment, something MT understood very well. All the same Hurd was clear that something would have to give. Following a meeting at his grace and favour country home, Chevening, he told the PM's Private Secretary privately: "We could not go on saying no on money, refugees and troops".

September 1992: An Ira Plot to Kill MT

Sometimes individual documents are held back from release when a file is made public, scrupulous officials leaving a note giving bare details as to dates, authors and recipients, grounds for closure. There are a few such in this file, dating from September 1992 when MT was due to visit the US.

One can make a good guess as to what these closures are about, because in 2014 the FBI released its file on MT, which showed they had received word of an IRA plot to assassinate her during the visit. The information was treated with the greatest seriousness, not least because it seemed someone in the FBI was giving help to the IRA, turning the case into a mole-hunt. Several IRA men in the US were being watched, with some difficulty; they were judged capable of the deed. The issue received personal attention from the FBI Director, William Sessions, who coincidentally (or not) met MT at a private dinner in Washington on 14 September and was disturbed to find no sign that she had physical protection, insisting that his concerned inquiries on this point be recorded on the file.

In the event there was no attack of course. MT did cancel a planned stop in Denver, though the reason is not stated. Eventually the IRA suspects dropped out of sight and were judged to have left the US. The file was closed in 1993.