MT's private files for 1990 - (4) resignation, murder and war

The summer months are generally the quietest in British politics, with Parliament headed for recess and the country moving into holiday mode, the media included.

In 1990 things worked out very differently, with a resignation, a murder and finally the outbreak of the first Gulf war occurring within a calendar month..

Jul 1990: Nick Ridley's Resignation & Consequent Reshuffle

No friend to unification

No friend to unification

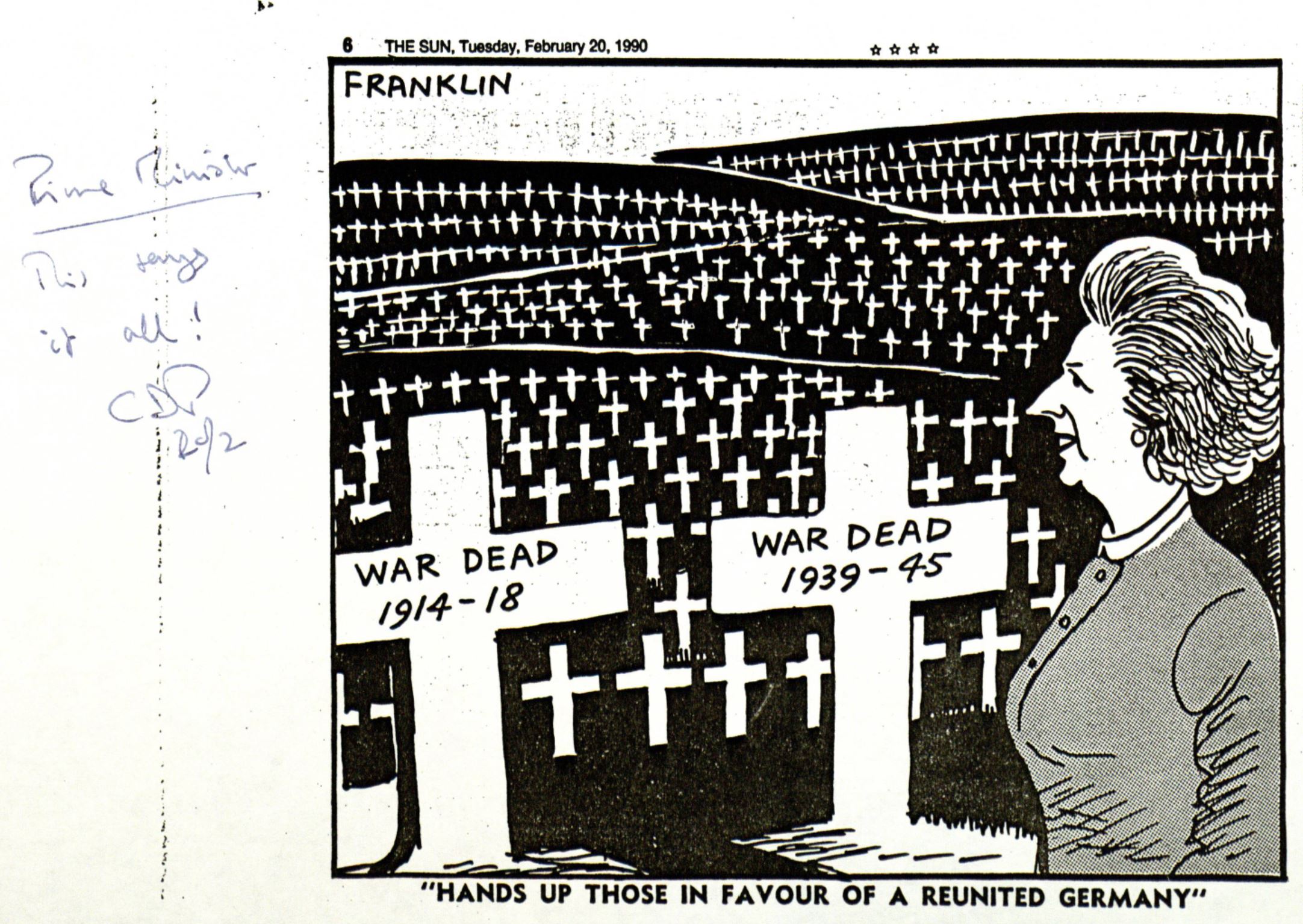

CDP sends MT a cartoon that "says it all"

We have only a handful of documents relevant to Ridley’s resignation over comments about Germany in an interview he gave to the editor of The Spectator (Dominic Lawson, son of Nigel).There is a brief handwritten note to MT from Charles Powell attaching a photocopy of the interview with the somewhat understated comment: “This looks like a banana skin”. At that early stage Powell was still trying to contact Ridley (who was in Budapest) for comment. MT and her entourage were themselves just back for the Houston G7 summit.

Ridley's downfall resulted from his comment that monetary union was “all a German racket designed to take over the whole of Europe … You might just as well give it to Adolf Hitler, frankly”. His remarks received a terrible press in the UK, almost all the papers demanding his head. Kohl’s office issued a statement descriving them as “scandalous and insulting”. Ingham left MT in doubt that significant damage had been done. Even the Sun found fault with the intemperate manner of the interview, and published a four page pullout “Why Germans are wealthier and smarter than us”. (The paper’s line grew a little more sympathetic to him after he resigned.) Ridley was not without public defenders – Jonathan Aitken and Teddy Taylor spoke up for him among MPs, and he had some press backing (eg, the Star). Also the No.10 postbag was heavily in his favour. But one person who offered him no public backing was MT.

It is often suggested, of course, that she shared Ridley’s view of the Germans, and that is surely correct. A cartoon sent her – by Powell – in March hints at the way she spoke and thought in private at this time. But she would not have been so careless as to use such words as he did in public.

Ridley had damaged her at a difficult time. And he had the potential to damage her further if he stayed. She was moving toward joining the ERM, having run out of alternatives. Would – could – Ridley have remained in the government when that event took place? We might have have been writing about his resignation in October, if we had not been writing about it in July. Although she lost a cabinet ally in Ridley, he was no more able to alter the fundamental direction of policy than she was and could well have made the final outcome more painful.

The Ridleys had been due to meet the Thatchers at the country home of the Keswicks in Oare the weekend after the resignation, but they tactfully pulled out. MT quietly had them to lunch at Chequers on Sunday 29 July. According to the diary of the official head of the FCO, MT declined suggestions that she ring Kohl to apologise, but there are two letters from her to the German Chancellor on 17 July plainly intended to take away the sting, one explicitly referring to the “unfortunate interview”, although it stopped short of an actual apology.

Ridley’s departure required a small reshuffle. Peter Lilley replaced him at DTI. One notable, and important, change also took place in the line up at No.10: Mark Lennox-Boyd departed as MT’s Parliamentary Private Secretary (PPS) to become a junior FCO minister, replaced by Peter Morrison. Lennox-Boyd’s sad farewell letter is in the files, as well as her long but unusually tardy reply in thanks, written to Lennox-Boyd and his wife together, friendly but a little embarrassed in style. Those in the know understood that the change was important. Whitelaw wrote congratulating her on the wisdom of the reshuffle, particularly as to Morrison, whom he called “a most inspired choice as he has that rare experience of both Govt and Party. He has also the advantage of seniority and maturity which will be great assistance to you”. Whitelaw was the very embodiment of Conservative conventional wisdom and it seems MT felt much the same. In her reply she said: “We are all delighted to have Peter here with us”.

Letters at this time from MT to the Chief Whip in the Commons, as well as to the chairman of the 1922 Committee, Cranley Onslow, show her on absolutely best behaviour, understanding of their work and struggles, the soul of consideration and tact. The entire Conservative Parliamentary Party was invited to receptions at No.10 that July. She really was trying.

30 Jul - 8 Aug 1990: Murder and Funeral of Ian Gow

Ian Gow was MT’s first and most successful PPS, in post for the whole of her first Parliament. The IRA murdered him with a bomb under his car at his constituency home in Eastbourne on 30 July 1990. His last letter to MT is dated 14 May, thanking her for inviting him to DT’s 75th birthday party at Chequers a few days before. It belonged in a long series in which he provided affectionate reassurance that bad times would pass and that resilience would win through. He was funny and frank. “How I wish that members of the Cabinet were more supportive. Geoffrey never speaks out. Nigel Lawson appears to be in a vault in Barclays Bank. [Lawson had accepted a job with its investment banking arm, Barclays de Zoete Wedd]. Some of the young ones have been taken in by Heseltine, but I think he will never succeed you. What saddens me most is the inflation. Lawson should have departed two years ago”.

Following his murder, on 30 July, Peter Morrison wrote MT a long letter of commiseration, which included an apology for the fact that “the loss of one of my greatest friends has rendered me pretty much useless during the course of today”. He had been due to meet Gow for tips on how to do the job. MT dropped everything and arranged to fly immediately to Eastbourne. She then attended the funeral a week or so later where she read one of the lessons. There are many details in the file, including the letters she wrote at the suggestion of the priest to each of the teenagers who acted as servers in the church on the day, undoubtedly an ordeal for them. After the service funeral guests went back to Gow’s home, and whether by luck or design, she and Geoffrey Howe (a great friend of Gow from schooldays on) managed not to be there at the same time, MT leaving before Howe returned from a Privy Council meeting on the Royal Yacht. She invited Jane Gow to Christmas at Chequers, an offer very politely declined. There was to be no Christmas at Chequers for the Thatchers either, as things turned out.

Aug-Oct 1990: Aspen & the Outbreak of the First Gulf War

After Gow’s murder Ingham urged MT to move swiftly on, a sound instinct as to her character and probably the politics too. Her old friend and speechwriter Ronnie Millar had a similar response. In any case events left her little choice. She was due to fly to Aspen for an international conference at which she would deliver an important foreign policy speech, along with President Bush. There would be days of visits to US government facilities as well as mingling with celebrities from the US political world attending the conference, many of them by now familiar faces to MT.

Then on Thursday 2 August, Iraq invaded Kuwait. We are releasing her rough notes in preparation for the meeting she immediately held with the President, of which the gist is: oil oil oil. The notepaper is headed quaintly “Elk Mountain Ranch”, the Aspen home of the US Ambassador to the UK, Henry Catto and his wife Jessica.

Given MT’s political problems at home, an immediate issue was whether there would be a “Gulf Factor” working in her favour, an electoral uplift conferred by the sight of the seasoned war leader once more heading the country at a moment of military crisis. By the end of August, Ingham was fairly clear there was not, at least none directly visible in the polls: he saw ‘confusion’ on this point. There seems to have been confidence that the war was or would work to her political advantage, if only by changing the topic of conversation and so obviously playing to her strengths. And there were clear indications of very strong popular support for the government’s policy, approval ratings of more than 80 percent. But clearly there was nothing remotely comparable to the “Falklands Factor” that operated so powerfully in 1982-83. And who could forget the lesson the British electorate gave Churchill at the General Election of 1945? Certainly MT never did.

Interestingly the papers we are releasing show that MT was cautious about making claims over WMD to justify military action. She rejected a paragraph on this topic drafted for her speech to the EDU on 25 August and showed reluctance to be drawn too far when interviewed by David Frost on 1 September, limiting herself to saying that Saddam could have a nuclear weapon in five years and explicitly rejecting Frost’s suggestion that it might be two. In her speech to the Commons on the recall of Parliament, 6 September, WMD did not merit a mention at all.

There is a valuable handwritten note by MT “Notes for reply to President Bush’s phone call Oct 1990”, setting out very clearly her reasoning at this point, especially the dangers of “playing it long” and the importance of not missing what she saw as the narrow window of opportunity to take military action before the summer heat made it all much more difficult for the allied military. There is an instance here of her occasionally erratic spelling, the word ‘Iraquian’ appearing at one point, curious in someone who read so much about Iraq and the Iraqi Government. (For convenience a transcript of this document is supplied. Note that there may be a second separate document at the end of the first, where the penmanship changes.)

One remarkable feature of the Aspen visit is that she evidently enjoyed it hugely. The thank you letters afterwards are full of interest and feeling. How could this possibly be? The trip followed immediately the terrible death of one of her closest friends, killed for his association with her, and a major war broke out at the same time. Was she heartless? Her detractors would say just that, but the answer clearly is ‘no’. She felt Ian Gow’s death very deeply. She was not in the slightest doubt that the war was a terrible thing. But always, her response to stress, to setbacks and horrors was to turn to her work, her great duties - onward, outward, upward. Nothing could quench her extraordinary spirit, until perhaps, finally, the loss of power removed the duties altogether and there was nowhere to turn, no real upward and onward any more.

Around this time she sent a kind letter to an old friend from the law, whose career as a judge was ending. She wrote: "All good wishes for your retirement. It sounds strange to say that because I view any prospect of retirement with distinct alarm. I prefer to be in "the hot seat" as you so aptly put it!" She understood full well this quality in herself.