MT's private files for 1989 - (5) foreign policy

The year 1989 was one of the most remarkable in modern history, the year that the Cold War all but ended, peacefully and on the West's terms.

Yet MT, who had seized the zeitgeist again and again in her career, who had fought for this moment as strongly as any of her contemporaries and with greater faith, was somehow left weaker and diminished.

The Old and the New Us President: Reagan Yields to Bush

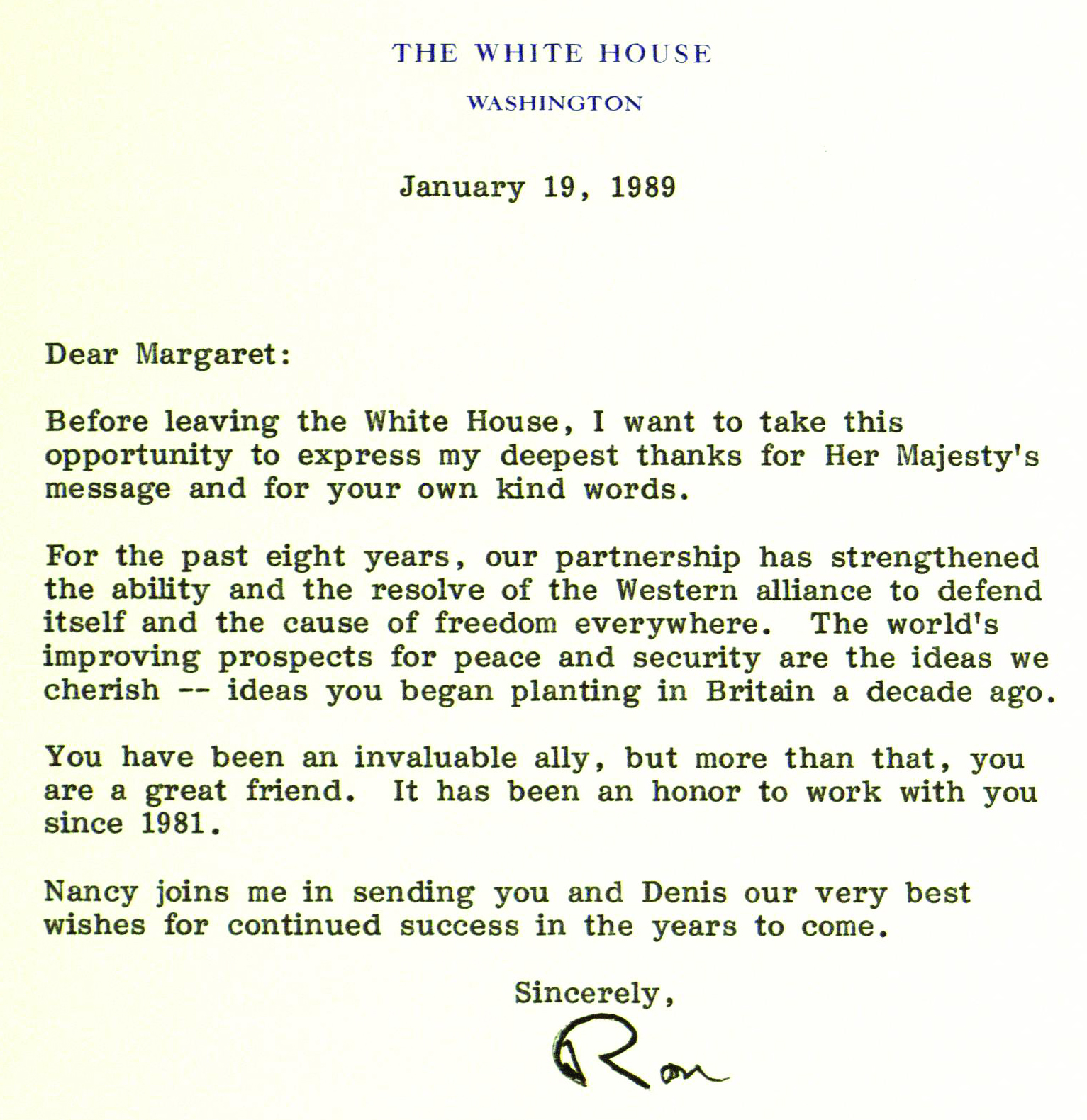

President Reagan's last message from the Oval Office

The year opened with the final bowing out of Ronald Reagan, who left office on 20 January. There was an exchange of messages – indeed MT was told that she received the last he sent from the Oval Office, shown here – but in truth she had said her farewells in an emotional visit the previous November. Attention had already turned to his successor, and inevitably the relationship struggled by comparison. After Reagan, there was really nowhere to go but down. The opening exchange of messages with Bush says it all. MT praised Bush’s “enormous experience in Government”, but found nothing else to say him about personally. To Reagan she wrote:

As you leave office, I wanted simply to say thank you. You have been a great President, one of the greatest, because you stood for all that is best in America. Your beliefs, your convictions, your faith shone through everything you did. And your unassuming courtesy was the hallmark of the true and perfect gentleman. You have been an example and an inspiration to us all.

A sense of discord hangs invariably over her dealings with Bush, of missed cues and temperamental distance, quite apart from significant differences on some questions of policy. Even the courtesies went wrong. When the Bushes visited Britain at the end of their European trip in May-June 1989, the President and First Lady wrote nice thank you cards to MT when they were on Air Force One flying home. But it took the White House a week to get even telegraphic copies to No.10, a fact noted by Charles Powell, let alone the originals, which took till the end of the month. One cannot blame the Bushes for that, although perhaps they could have learned how to spell ‘Denis’.

More encouraging were two long telegrams from the US Embassy in London reviewing the scene in London on MT’s tenth anniversary, ostensibly for the benefit of the State Department but supplied to MT via Powell on a “strictly personal basis” by Ray Seitz, then number two at the USE, later Ambassador himself. They are of course immensely flattering, though not without insight or occasional bite. “Day by day and bit by bit, Britain is moving into Europe and Mrs Thatcher’s distrustful resistance to things cross-channel struggles against the current of Britain’s inevitable long-term interests”. MT may not have approved either of Seitz’s view that “it is not altogether bad to have Britain arguing somewhere to the right of the US” – a statement that could not have been made at all during the Reagan Administration, and which disturbed her when she heard it, or something very like it, voiced by President Bush himself, when he described her as “an anchor to windward”. Her tenth anniversary drew a warm letter from the President, who called her “a daily inspiration”, but oddly he also sent her a letter in October when she reached thirty years as MP for Finchley, an anniversary scarcely anyone remarked on in Britain, outside of Finchley that is.

Reagan still figured in her life as a private citizen. He visited London in mid-June and she arranged a dinner party for him at No.10. Among the guests was Richard Todd, the British actor who had starred with him in the 1947 film, The Hasty Heart. Set in the Far East, it was actually filmed in London, giving Reagan an experience of Attlee’s socialist Britain that served him later as a cautionary memory. In September she wrote him a get well letter after a riding accident in Mexico required him to have brain surgery, an injury that some later linked to the onset of his Alzheimers. Replying, he joked about how much he missed Economic Summitry.

End-Game: Gorbachev, the Fall of the Berlin Wall

For much of 1989, MT was in the odd position of having relations almost as close with the Soviet leader with as the American. The new Bush Administration was significantly cooler to Gorbachev than its predecessor, increasing her potential value to the Soviets as a go-between. The first Bush-Gorbachev summit did not take place until December 1989.

But even so there was an embarrassing Cold War incident. Britain expelled some Soviet diplomats in Janauary, aiming to do so in the quietest and least damaging way. Given that Gorbachev was due to the visit the UK in April, postponed from the previous year owing to the Armenian earthquake, this was a difficult manoeuvre. It did not help that the story leaked from the Foreign Office, or so No.10 thought. The Soviets eventually retaliated in May 1989, after the Gorbachev visit, the first formal acknowledgment that there had been expulsions by the UK.

There was tough talking by MT to Gorbachev during his visit. She carefully prepared speaking notes for some harsh words she wanted to say to him about chemicals weapons, which she certainly delivered; the notes clearly match the official record of the conversation held in files at Kew.

The main positive headline from the summit was the announcement that The Queen would visit the USSR the following year. But press treatment of the Gorbachev visit was underwhelming. It had begun to be taken for granted in the West that East/West relations were fundamentally stable and that business would be done.

The sense of stability was misleading, of course. Only months later we have her notes of a phone call from Helmut Kohl on 10 Nov 1989, the day the Berlin wall fell, describing the situation with vivid detail of his walk through the streets of Berlin, and ending “Gorbachev watching things anxiously/ extremely concerned”.

Among the papers in her private files is a note by Robert Conquest, a long-term friend and ally, one of the people who helped her write the speech that caused the Soviets to dub her the “Iron Lady”. He clearly dismayed her by predicting that German unification could not be long delayed, and that an “effectively neutralised Germany” would leave NATO because the Soviets would not allow NATO’s frontier to be on the Oder. The stage was being set for one of the great debacles of her foreign policy, her prolonged and unsuccessful resistance to German unification, which alienated many who were friends, quite apart from those who were not.

The End of History, and Its Beginning: Fukuyama and the French Revolution

The slow then fast collapse of the Soviet Empire during 1989 generated a vast literature, among it a piece which became instantly famous, and has remained so - Francis Fukuyama’s article in the National Interest, “The End of History?”, later expanded into a best-selling book. Powell sent MT a copy of the article on 4 September, with the following brief summary:

Fukuyama's thesis is that history has been the struggle of rival ideologies, a struggle which western, liberal democratic ideas have now convincingly won. Fascism and Communism have been seen off: although nationalism and religion might seem competitors, they are not so in practice: and it is unlikely that new ideologies are going to emerge. He draws the conclusion that history is at an end, in the sense that the great ideological conflicts are over and that the whole world is now moving more or less rapidly to adopt liberal democratic ideas. He adds rather facetiously that the consequence will be centuries of boredom ahead. But this is not essential to the argument.

Perhaps out of tact, Powell did not mention that Fukuyama’s model for the future of the democratic world appeared to be something very like the EC on a world scale. Even without that fact, it is hard to imagine an argument more calculated to irrirate MT than Fukuyama’s. No prizes for guessing what she must have thought of the following professorial reflection:

The end of history will be a very sad time. The struggle for recognition, the willingness to risk one's life for a purely abstract goal, the worldwide ideological struggle - that called forth daring, courage, imagination, and idealism, will be replaced by economic calculation, the endless solving of technical problems, environmental concerns, and the satisfaction of sophisticated consumer demands.

For MT, politics - life itself perhaps - was a constant call to battle. Finally that is why she was so wrong-footed by the end of Cold War. She itched to make a speech denouncing Fukuyama's ‘heresy’ (as the director of the Conservative Research Department called it, supplying ammunition). Her Conference speech was identified as an ideal vehicle and Hugh Thomas approached to assist by Whittingdale:

She strongly believes that the battle is not won and that there are always evils in the world to be opposed. Obvious current examples are those who give support to international terrorism and those who allow production and distribution of hard drugs.

Her 1989 Conservative Conference speech was unusual in having a theme geared to international developments, “The Age of Conservatism”. Fukuyama fitted in easily, but British politics rather less so, which was quite a problem in a speech traditionally geared to the domestic audience. Ingham wrote her a note discussing how it might best be done, but it reads as if she was obliged to make the best of a bad job. Domestic issues were underplayed because the government was struggling with them. She was no longer able to command the agenda as easily as she had.

Earlier in the summer claims about the beginning of history, or at least that of the modern world, had been in her sights. The G7 Economic Summit that year was in France, and the French Government dovetailed it with a grand celebration of the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution. MT, of course, attended, but not for her polite remarks or easy quotes from Wordsworth: “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive”. (For all her love of poetry she was never a great fan of the English Romantic poets, perhaps because of the revolutionary taint.) She gave interviews to the French press in which she bluntly challenged revolutionary claims for the Declaration of the Rights of Man as the origin of modern notions of human rights. Friends wound her up a little: Victor Rothschild sent her a Scarlet Pimpernel plant “which arrived just in time for me to wear a buttonhole to go to France”, as she wrote in her thank you note. She received a letter of congratulation afterwards from the Duchesse de Gramont, whose namesake had been at the cutting edge of the revolution, as it were, in April 1794.

Having had her fun though, MT was at pains to close the argument down, stressing what a marvelous summit it had been, brilliantly chaired by President Mitterrand, and so on. Drafting her statement to the Commons afterwards, Powell told her he had left out all reference to the bicentennial celebrations “to avoid hoots”.

Ancien Regime France had figured earlier in the year too, when she had chosen to turn a bilateral with Mitterrand into a weekend visit to France, an unusual thing for her which perhaps should be seen as a practical expression of the Bruges approach. She was given a tour of the Château of Vaux-le-Vicomte by its aristocratic owners and our Ambassador in Paris hosted a political dinner for her which Barre and Chirac attended, as well as "some new faces", as MT put it in her thank you letter, adding with a certain wariness: "There is no doubt that Madame Cresson is a formidable politician". She even took in a Gauguin exhibition, and was at pains to draw the moral, telling the Ambassador that it all served to "remind one of the strength of French culture. Who could possibly want to submerge that in a European blancmange!"