MT's private files for 1989 - (3) Nigel Lawson's resignation

The single biggest blow MT suffered in 1989, and there were many, was the unexpected resignation of Nigel Lawson on 26 Oct 1989.

Her leadership never entirely recovered.

Run-up to the resignation: MT, Lawson and Walters

MT's note of their conversation

MT did not want Lawson to resign, quite clearly. Powell’s reshuffle note is surely powerful evidence of that. Why she was so keen to keep him at the Treasury is a little harder to say. Their semi-public quarrels, during 1988 especially, had been shattering. MT clearly believed Lawson’s conversion to an exchange rate target lay behind the recurrence of inflation, although it was essential for her, of course, to do her best not to say so in public. Walters recommended she blame it on the cut in interest rates after Black Monday: “If you need a rationalisation, this is the best one to use”. One gets a hint of how the two of them spoke of Lawson between themselves from a cutting he sent her on 7 October and which she kept in her personal papers, Andrew Alexander’s column in the Daily Mail. “Mrs Thatcher made a mistake in the summer reshuffle by saying to Mr Lawson that he had got us into this trouble, he must get us out. That left Mr Lawson free to insist the he must be allowed to do it on his terms. / She should have sacked the so-and-so then”.

And yet, however much she may have groused, MT had not sacked Lawson, even if Walters thought she should. Perhaps she had an instinct that the political damage would be too great. No minister was closer to the heart of Thatcherism than Lawson. In many ways, in economic policy at least, he was the man who had made it all happen, the minister who had done more than any other to turn proposals into plans and then into concrete political fact. Whether personally close or not, they shared ownership.

In fact until the “Madrid Ambush”, relations between No.10 and No.11 had been smoother that year than at most points during 1988. Press stories about rifts between the two continued to appear, but that was in part because the press was looking for them. One such during the European Elections was so lacking in substance as to draw a furious response from No.10, Ingham arguing that it amounted to outright fabrication, the work of “an inaccurate, prejudiced and malicious operator”. The budget was seen as dull, but in the circumstances that was probably a virtue. Economic news during the year was often bad, with inflation rising, sterling under pressure, the trade deficit at record heights and interest rates eventually peaking at 15 per cent in October, but one lesson MT and Lawson had both learned in the early 1980s was the importance of sticking to the hymnsheet when the numbers were bad.

In 1989 the arrival of Alan Walters really did have an incendiary effect, because it created new opportunities for the press. Journalists found a vein of statements that he had made before resuming his role at No.10 on 1 May and they needed no encouragement to dig. One item in Walters’s private papers is a long letter from Paul Gray, the No.10 Private Secretary for economics affairs, explaining the problem to him point-by-point, written only days before the final crisis with Lawson. There is a copy in the official files at Kew, with an accompanying note by Gray for Turnbull saying he had sat with Walters and talked through the letter, finding the economist ‘unrepentant’. This is not to say that Walters desired the outcome or that he expected it, still less that MT attached any blame to him. She certainly did not, quite the opposite. But the No.10 machine seems to have been less certain.

MT's Memoir of Lawson's Resignation: When Was It Written?

MT was always keen to stress afterwards how unnecessary Lawson’s resignation had been, going a step beyond not wanting it, or expecting it. A sense of astonishment, disbelief, became part of her defence against Lawson’s criticisms, a way of denying there was any substance to the whole thing. She came close to professing outright mystification.

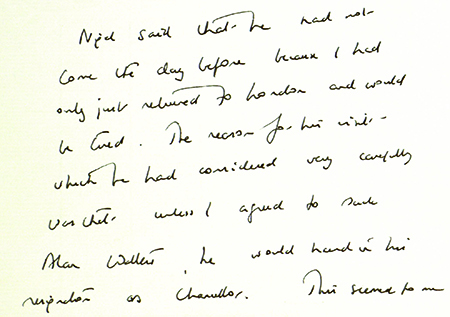

This is partly the perspective one finds in the note of events that day that she wrote afterwards, but a note of anger is strongly present also, a feeling she did her best to conceal in public. She occasionally prepared these aide-memoires at seminal moments of her premiership (e.g., the Fontainebleau European Council).

One must say immediately that the Lawson memoir is incomplete and that the date of composition is doubtful. It seems to have been begun close to the event, but in its present form was mostly written some years later, probably in early 1992. It was seen in her study at Chester Square around March 1992 by a member of her memoirs writing team (the author of this page), and was radically incomplete at that point, obviously incomplete at a glance. She had not even finished the first page, the document ending around where it says ‘8.50’. MT acknowledged the problem and said something like: “Yes, I know - it’s a shame, it would have been useful, I just didn’t get time to finish it”. But now, the Lawson note runs to three pages. Clearly she found time to add to it, though it still isn’t finished as an account of the day, or anything like.

There is a story in Woodrow Wyatt’s diary for 1992 that she told him she had just destroyed some notes on Lawson’s resignation. What can this mean? There is a answer consistent with what we have in front of us, though it is wholly speculative. She sometimes jotted skeletal contemporary notes to jog her memory before sitting down to write up a fuller account. She did this for her memoir of Chernenko’s funeral, for example; we know that, because we have the sketchy notes as well as the finished thing. Perhaps something like those notes existed for Lawson, enabling her to continue the fuller account years after the event, jottings that she then destroyed because they had served their purpose? And perhaps those jottings were incomplete to start with? She was always clear that she had run out of time.

One other feature of this short Lawson note is a slight tendency to tidy things up. The account in her memoirs was based on what was then her strong personal memory of events only three years earlier, secured in face-to-face conversation. She clearly said she had heard Lawson wanted to see her when she was having her hair done. Crawfie had brought the news. But in this note, there is a more ‘Prime Ministerial’ tone. The hair set doesn't entirely disappear, but the bearer of the news is the august figure of Andrew Turnbull, her Principal Private Secretary.

The memoir is incomplete, but she spoke candidly of that day in an off the record interview with Kelvin Mackenzie on 6 Nov which we are publishing for the first time. She described DT coming home at around 8pm not knowing quite what had happened:

I went upstairs, phew, quite a day. He came in and we sat down and he asked what had happened and I told him. In a matter of minutes both my children were on the telephone. "Mum, we've heard the news. Are you all right?" Do you know that made me more cheerful than anything else. "Mum, are you all right? Do you want me to come round?" Just marvellous to talk to them. My son had seen it in America. "Mum, are you all right? Don't worry, you know we love you". It means more to you than anything else in the world. Then I talked and Denis was in for supper. So I must have got some supper. Someone's got to do it. And then there's nothing that I could do about what had happened, about the day. I just had to get on. It was pretty busy day. I hadn't long been back from Malaysia and I had had about no more than four hours sleep. I think I must be the best adrenalin producer in the United Kingdom. I think I must have a super adrenalin producing system. I didn't feel tired.

Aftermath: Parliament, TV, Friends

You might say there were four ‘big’ resignations from the Thatcher Governments: Carrington in 1982, Heseltine in 1986, Lawson in 1989 and Howe in 1990. Of the four, a good case can be made for saying that Lawson’s was the most damaging.

Howe’s has received more attention, understandably enough, but in truth it would not have mattered nearly as much if Lawson had not gone first. Even the sequence of events in 1990 strongly echoed that of 1989, particularly the triggering of a leadership election as a result of the resignation. And without the 1989 leadership election, it is far harder to imagine events working out as they did in 1990. Although no one could have known it, Lawson’s resignation set up a dry-run.

There is good material on the immediate impact in a series of notes to MT from Lennox-Boyd in which he relayed reactions from Conservative MPs in phone chats over the weekend. Many of them will have been getting constituency feedback, as well as giving their own views. Several interesting themes emerge. Lawson’s successor, John Major – switched from the FCO, which he had occupied only since July – was now in a very powerful position relative to her. She could not afford to lose him. Lawson himself had never cultivated backbench opinion and at this point it showed: he had no great body of personal support. But the impression of mismanagement on the part of No.10 was strong. She was going to pay a price for his departure.

As luck would have it, MT had a major tv interview scheduled the weekend after the resignation, with Brian Walden. Walden was generally considered the most sympathetic of tv interviewers from her point of view, and Ingham billed him as such in briefing, but the files suggest a certain distance was emerging between them. She read the transcript of an interview he had conducted with Ken Baker over the summer and wrote on it: “Not a good interview – just brow-beating”. They had held a private meeting on 2 Oct at which Ingham expected Walden to urge on her “a slowing down without a loss of dynamic”, unlikely to have been to her taste.

Events were moving fast and there was some confusion, with the result that important briefing material did not reach MT till after the interview, which purported to be broadcast live on the Sunday morning, but which was actually filmed the previous morning, an arrangement with which she was uncomfortable, fearing leaks. Her annotation on the late arriving document was sharp. She rarely criticised the No.10 machine, and she rarely had reason to; this instance therefore stands out. Wyatt’s diary suggests Walden relayed an outline of his questions to her through him, and got guidance as to her replies, which would suggest she did not go into the interview wholly in the dark, but even so, she was probably not as well-prepared as she would have liked to be.

The Walden interview drew mixed reviews, but for certain it was far from the kind of sympathetic treatment Ingham and others expected from that quarter. MT’s stance of mystification at Lawson’s resignation did not work well, the performance echoing her struggle to rebut Michael Heseltine’s attacks during Westland when she declared him a “rebel without a cause”. Her repeated claim that Lawson's position had been 'unassailable' produced an almost comical effect. She had little or no defensive game; attack was her only defence, so she struggled when, for whatever reason, attack was not an option. But some of Walden’s questioning generated sympathy for MT, registered in letters from her friends, particularly the following exchange:

Brian Walden

You come over as being someone who one of your Back Benchers said is “slightly off her trolley” , authoritarian, domineering, refusing to listen to anybody else. Why, why cannot you publicly project what you have just told me is your private character?

Prime Minister

Brian, if anyone is coming over as domineering in this interview, it is you, it is you, hammering things out instead of just talking about them in a conversational way.

Lord Hanson wrote to her calling Walden a “rude, arrogant and stupid man”. Australian tv mogul Bruce Gyngell was equally aggrieved and wrote describing him as "extremely sexist". He hit on an aspect of the interview MT herself dwelt on, the idea that only a woman PM would be called 'authoritarian' for taking a strong lead.

Compounding the problem on Sunday 29 Oct was press coverage of a speech by Howe widely seen as a warning to MT. The No.10 Press Office sent her a note the following week piecing together what had happened, journalists telling them Howe’s “acolytes had telephoned the media” to promote the speech and offer ‘spin’. Nevertheless, MT was firmly advised by Whittingdale and Lennox-Boyd to keep on terms with Howe. The appointments resulting from Lawson's departure suggest she already understood this. A close ally of Howe's, Tim Renton, was made Chief Whip in succession to David Waddington who had been made Home Secretary. Since Renton was reckoned no friend of hers, this appointment only makes sense if it was done at Howe's request. As Leader of the House, of course, Howe worked closely with the Chief Whip, so it would have been difficult not to ask his view.

Tim Bell sent MT interesting advice at this point too, via Charles Powell, the gist of which was that she faced the possibility of defeat at the next General Election without big changes to focus on presentation, inevitably at the expense of her existing role in determining policy and conducting foreign affairs. It will have been an unappealing prospect to her, and Tim Bell would have known it.

Walters had resigned the same day as Lawson, insisting on his own departure which MT had not sought, though it certainly eased her situation. When he cleared his desk the week after he found a four page handwritten letter from MT of which no copy survives in her files, but which we release from his. A minute from Turnbull to MT noted how pleased Walters had been to receive it, and that he had decided on the advice of No.10 to make no public statement about events, turning down also the offer of a regular column for The Times, doubtless at considerable personal loss.

There are further notes by Lennox-Boyd, notably on 8 November when he told MT that most Conservative MPs thought “the immediate problems caused by Nigel’s resignation are now over”. Unfortunately for her, this proved to be an over-optimistic judgment.