MT's private files for 1988 - (8) Life at No.10

For all the stresses of the year, there are a fair few hints in the files that MT rather enjoyed herself at times.

Arts & the Woman: Fortes & Rothschilds

Part of the Thatcher realignment was a new emphasis on the arts and, in a modest way (very much on a budget), the arts began at home. The woman who bought her own ironing board when she became Prime Minister, for fear of seeming extravagant, finally gave No.10 a makeover in 1988, including her own study, the stairs and landings, as well as the impressive suite of state rooms on the first floor. Little decorative work had been done at No.10 since Ted Heath's time, so paintwork, gilding and fabrics were refreshed and replaced. The lovely White Drawing Room got a new plasterwork ceiling, suitably ornamented with sculptured emblems of the British Isles. Much in the way of furniture and other fixtures came from existing government collections. No files have been found in her personal papers, nor do any seem to have made their way to Kew in the official archives, though paperwork there must have been. The work began in earnest when MT returned from her tour of Australia and the Far East in August. She would pop in from time to time to monitor progress, happily chatting to workmen and looking at samples. Olga Polizzi masterminded operations. Her name often appears in the diary that year, along with other members of the Forte family, who had been friends for decades. Possibly MT’s first ever photo opportunity, in the early 1960s, was a shot of her sliding down the artificial ski slope at Battersea on a sledge. The smiling man behind her steering the thing was Olga's father, Charles Forte.

What we can trace on paper are the many efforts MT made to borrow new pictures for the redecorated rooms, particularly at the end of the year when she was, frankly, on the scrounge. She visited the Royal Society in late September to deliver her landmark speech on the environment, but such weighty matters did not drive from her mind the itch to borrow some pictures of great British scientists. In his letter of thanks the President of the Society, Sir George Porter, wrote: “If you will let us know what portraits you would like to have, I will see what I can do” (28 September). The following day Charles Powell sent her a minute about a dinner engagement with the Carringtons that Saturday. Just retired as Secretary-General of NATO, Carrington had moved into a new strategically significant role as chairman of Christies. They plotted how to persuade one of his guests, Evelyn de Rothschild, to loan a Turner that had just failed to sell. The crucial thing was not to mention Jacob Rothschild it seems. That may have been a little difficult, because she had tapped Jacob for help earlier in the month. The Thatchers had made a private visit to the National Gallery to see an exhibition of French art from Russian collections, guided around by Rothschild in his capacity as chairman of the trustees, along with its director Neil MacGregor. The two men were given a return invitation to No.10 to study the “new look”. She turned down the suggestion that her letter should explicitly ask for help, simply adding: “P.S. I understand you are coming to visit the Pillared Room to-morrow”. They would get the hint. A third Rothschild was loaning things too: Jacob’s father, Victor, stumped up more silver that year, some Queen Anne candlesticks.

A rather less expensive picture came her way at the beginning of the year, as a gift not a loan. Willie Whitelaw organised a cabinet dinner to celebrate quietly her passing Asquith’s record as the longest serving twentieth century Prime Minister on 3rd January. Between inviting her and the dinner actually taking place, he had suffered his stroke and resigned, though he remained Deputy Leader of the Party. The cabinet presented her with a watercolour of No.10 by Nick Ridley - not a great work perhaps, but very pleasing to her. In truth, for all the shameless manoeuvres to borrow a Turner and a Reynolds or two, she was always rather inclined to what you might call the “it’s-the-thought-that-counts” school of art criticism. Her thank you letter to Whitelaw has a wistful element to it, as she reflected on how warm and relaxed the occasion had been and added: “what a pity we don’t meet together more often for convivial occasions. But perhaps there isn’t time”. One wonders whether things might have worked out better for her if she had made the time. Barely was the 1988 celebration out of the way than another letter arrived from Whitelaw inviting her to a reception at the Carlton Club to celebrate her tenth anniversary as Prime Minister, in May 1989.

Another near obsession during the year fitted the new emphasis on the environment: she participated in many tree plantings. Gladstone was famous for cutting trees down at every opportunity, so perhaps she was levelling the Prime Ministerial score. Huge numbers of trees had been destroyed across southern England during the great storm of October 1987, many of them in places the Thatchers knew well. There was some real tragedy too. The woods at Lord De La Warr’s Kent estate suffered devastating damage and in a state of despair he jumped in front a train at St James’s Underground Station in February. MT wrote to his widow and attended the memorial service. Several of the themes mentioned above converged when she went to Hartley Shawcross’s country house at Friston for lunch before a trip to Glyndebourne to see La Traviata at the end of July. (Another option for the opera was Nigel Osborne’s The Electrification of the Soviet Union, but for some reason that didn’t take her fancy.) There was local tree damage to discuss, Olga Polizzi was there with her partner William Shawcross, also John Le Carré and his wife. Her thank you letter mentions how much she enjoyed talking with Le Carré.

At the very end of the year she was at West Wycombe as a guest of Sir Francis Dashwood, a trustee of Chequers. She planted more trees of course, and met also a Cameron-era minister, Hugo Swire. Swire was there as a family friend of the Dashwoods: it is striking that few of the younger party officials and special advisers she met in her work during 1988 went on to successful political careers, their prospects destroyed by Tony Blair's New Labour. His landslide victory of 1997 was a decade away, as yet unglimpsed, but you might say it was beginning to cast a shadow. The Cameroons were fortunate to start their careers a little later.

Media: The BBC & David Frost

Less happily there were some bumpy moments with the BBC in 1988, one of them very personal. A short file released at Kew shows that the Attorney-General was asked to advise whether libel proceedings might be commenced against the Corporation for an item on the Today programme in January, a winning entry to a short fiction contest read out on air that imagined MT legalising hard drugs. (Entitled "Thatcherism the Final Solution", it included lines like "Crematorium shares surged ... the unfit died of freedom".) The Attorney thought the item was defamatory, but the file ends abruptly with MT asking her officials not to proceed. Her private papers show there was a sequel, in the form of a grovelling letter from the chairman of the Board of Governors, Duke Hussey, to Denis Thatcher, who had taken up the case on his wife's behalf. “I really do not know what to say. If this had been about my wife I should have been absolutely livid. ... We have a very long way to go and it is going to take a long time”, Hussey wrote lamely. There is a note a few weeks later from Archie Hamilton of a private meeting of Conservative backbenchers which Hussey attended. He was given an unpleasant time, particularly by Norman Tebbit, “in abrasive form”, who had his own unhappy history with the BBC.

MT's last interview of 1988 was given to TV-AM on 30th December, with David Frost doing the honours. Ingham and Powell both tried to block this interview, but could not talk her out of it. They disliked the timing for one thing - a major TV interview when she should have been resting - but more than that they seem to have disliked and distrusted Frost himself. Ingham recalled previous interviews where he had let them down. Frost had raised the Belgrano issue without warning, for example, and shocked her on air by telling her that people were calling her "That Bloody Woman". He predicted Frost "coming over all smarmy at the end" to ask questions about her hopes for 1989, on looking forward to becoming a grandmother, and so on. MT insisted on going ahead, telling them that she was not doing it for Frost but for his boss at TV-AM, Bruce Gyngell. Smarmy or not, Frost was also a big figure in US broadcasting, courtesy of his famous encounters with Nixon, and the interview would air over three days on the NBC breakfast show. More than that, he was thought to be personally close to the incoming President, as even Ingham acknowledged. It is not altogether surprising that, for once, the veteran Press Secretary lost the battle.

Partying: Showbiz

If you are powerful enough to remake British politics and rebuild the economy too, one would have thought you could throw a good party. In November 1987 No.10 began planning for a reception to say “thank you” to 45 showbiz personalities who attended the Wembley Rally during the 1987 General Election, a miscellaneous collection of comedians, newsreaders and other “middle-brow rather more than high-brow” folk who would be easily recognised by the public as they trooped through the famous front door, and hence do MT much good on tv.

The Political Office was enthusiastic, but MT decided they needed more names. The rooms were too big for a mere 45. She promised to come up with a list, and deliberately crossed some prominent people off an earlier reception in order to reserve them for this glitzy occasion (eg, Anthony Hopkins, Antony Sher, Derek Jacobi). Further names, pages and pages of them, then got added by the Office of Arts and Libraries, many of them, sadly, of the highbrow variety (sundry Frinks and Freuds). A few more came from John Whittingdale, the new Political Secretary. He was not then the grizzled elder statesman of the present day; this was the young man whose evenings were spent watching Meat Loaf at the Hammersmith Odeon. His idea of a good party was to invite Paul McCartney (“Con supporter”), Freddy Mercury and the Jaggers. Just to be helpful he tracked down the names and addresses of their agents.

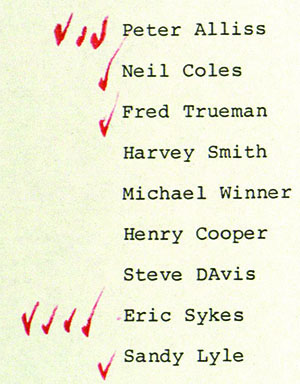

At this point, DT got involved. Generally he appears in the files scribbling assent to attend this or that engagement, often with ironic complaint (“Yes - as if I had a choice”). On this occasion he was much more engaged, addressing a long note to the Private Office explaining that “I find it unpleasant and embarrassing to entertain those who publicly insult the P.M. This list therefore needs some careful checking in this regard”. And what he he meant by that was checking it himself. He went through the list adding ticks, crosses and question marks according to a self-evident system he nevertheless took the trouble to explain, the better to rub it in. Golfers did well, and some in the acting profession. A couple of Scots got a line straight through them, while he handed double question marks to Gilbert & George (billed obscurely as “image makers”) and queried Paul Daniels, Jan Leeming and Shirley Bassey. He quite liked Dame Judi Dench and Richard Wilson (one tick each), but his absolute favourite was Eric Sykes, who got four.

In the event the problem of inadequate numbers was solved in a simpler way: No.10 set aside its now vast list, its fantasy party, and invited the original 45 plus the British Winter Oympics Squad. For some reason the list does not include the best-known member of the Squad – Michael Edwards, “Eddie the Eagle” – who finished last in the 70m and 90m ski jumps, but who made up in entertainment value for what he lacked in competitive clout. Perhaps he was busy that evening. Certainly many ministers were. They proved so difficult to rope in that Archie Hamilton had to beef up the home side by inviting the Parliamentary Skiing Team, who had spent so long on the slopes that year that they beat the Swiss at their own game, a rather embarrassing achievement for supposedly hard-working legislators. The upshot was that Ronnie Corbett rubbed shoulders, as it were, with the Earl and Countess of Verulam. Given all the grand plans earlier, it must have been a bit disappointing.