MT's private files for 1988 - (3) the NHS review & reshuffle; the economy

Quite apart from the inevitable strains arising from its massive third term legislative programme, a couple of big issues wore away at the government's aura of mastery during 1988. Winter troubles in the NHS helped to trigger a major review of the NHS at the end of January. But the review made poor progress and six months afterwards, MT split the massive Department of Health and Social Services, demoting and humiliating its Secretary of State, John Moore - a man formerly reckoned a close ally, even possible successor.

The booming economy was central to the government's standing, but problems were beginning to show.

Health & Reshuffle: announcing the review, splitting the department

One indication of the strength of the government’s position at the beginning of the year was the decision in late January to launch a review of the NHS. Ingham sent MT advance warning of a Sunday Times poll on 31 Jan that showed, the paper thought, public support for the step, at a time when the Conservatives had a lead of 14 per cent over Labour (50 Con 36 Lab 12 All) and the NHS had pulled well ahead of unemployment to become the most important issue facing the country in the eyes of voters.

Given the huge legislative programme already underway, the totemic significance of the NHS and the fact that a review had not featured in the Conservative manifesto, this was a bold and risky step. MT announced the decision in a BBC TV interview with David Dimbleby, an altogether stressful experience. She disliked big interviews at the best of times, and her last encounter with Dimbleby, at the very end of the 1987 campaign, had almost ended in disaster when she had made her gaffe about people who “drool and dribble they care” – a phrase she immediately retracted, with apology, and which she was lucky not to have hung around her neck as a permanent exhibit of Tory heartlessness. MT told friends who wrote praising her performance: “I hate these interviews. You never know how they are going to turn out!”, and “I am always very nervous at the beginning of these interviews – but gather strength as they proceed”. She seems to have been happy with this one.

The Health Review was a highly complex, government-led operation, naturally enough, so it does not feature much in MT’s personal and party files. There is some revealing material from the Policy Unit and Political Office though, strongly suggesting that they were struggling to get a handle on it and feared that momentum would be lost. One problem clearly was the scale of the task. A snowdrift of paper descended on Downing Street; one minute with attachments runs to 103 pages, while another, three months into the review, shows MT not even agreeing with the Policy Unit’s account of what had already been decided.

In summer 1988 she made a change, splitting the DHSS into a separate Department of Health and Department of Social Security, assigning the sitting Secretary of State, John Moore, to the Social Services side and making Kenneth Clarke the new Secretary of State for Health. This was done as the centrepiece of the annual government reshuffle, although stories that the department might be split first surfaced in a leak to the Guardian in April. It was a year of leaks, some from within No.10. Sometimes reshuffles are thoroughly documented in the Thatcher files; this one sadly is not. We do, however, have one intriguing document, a marked up copy of the list of ministers showing what appear to be reshuffle moves not far from what the ones finally made, too close certainly to be mere musings. It is probably an aide-memoire drawn up in a meeting by MT’s Principal Private Secretary, Nigel Wicks (a horizontal line seems to mean a sideways move; a cross – dismissal; an upwards arrow – promotion; some ministers get more than one).

If this document is a guide to her thinking, at one point she was contemplating moving Moore but not replacing him with Clarke. Instead, two or possibly three other cabinet ministers were in the frame to move – Paul Channon, at Transport, Norman Fowler, at Employment (the former DHSS Secretary of State), and John MacGregor at Agriculture. In the end all stayed put, but it is possible she thought of MacGregor for Health. He had impressed many as Chief Secretary before the election. Or was a return to his old department (or part of it) on the cards for Fowler?

There is, incidentally, one sad item in the files from John Moore, a letter he sent her in October thanking her for being understanding in a bitter little dispute over benefit uprating at the end of the spending round. MT had warned him against letting himself “get a little trapped in a departmental view”. She may indeed have been understanding on that occasion, but the dispute told against Moore. She dropped him from the government altogether the following summer.

There are some interesting points in the reshuffle document relating to the junior ranks too. Many of the changes suggested in the document actually took place, but a few did not. One of the non-events was a sideways move for Edwina Currie, a Parliamentary Under Secretary of State at DHSS whose career was ended by the salmonella in eggs affair in December 1988. Iin fact it looks as if an upwards arrow was replaced with a sideways line for her, so promotion may have been considered too, something several Conservative newspapers had called for - a fact to which Ingham's press digests brought MT's attention. If Currie had been moved in July, the ousting would not have happened, and her career might well have progressed a lot further than it actually did. MT is often criticised for not doing more to advance women in politics. Much of that criticism is unfair, because she could not give jobs to women MPs who didn’t exist and there were pitifully few to choose from, a problem not of her making. But there is surely some case for thinking she might have done more for Currie. MT did not push her out, but nor did she protect her. It is interesting that Ingham’s press digests show him struggling to take the egg story altogether seriously, at least in its early stages (“Curried eggs not so hot a story today” – 7 Dec, “Eggs off the boil but not quite off the menu” – 8 Dec).

If the note is to be credited, another non-move was Lynda Chalker, a Foreign Office Minister of State, marked for the chop but reprieved. Howe would certainly have done his best to protect her, as he was to do the following year in the reshuffle when he was himself removed from the FCO. Among juniors who were removed, on the other hand, no fewer than four of them were among those who spoke at a meeting between MT and all her junior ministers in Jan 1988. It is often said that she liked a good argument and did not hold it against people when they stood their ground against her and made a strong case. It was perhaps not so on this occasion.

The Economy: Highs and Lows

Underpinning the Conservatives’ impressive poll ratings in 1987-88 was the strong performance of the economy. If MT presided over a British miracle, economic transformation lay at the heart of it. But perhaps miracle talk is what economists call a lagging indicator: by the time you hear it, the peak has passed. As 1988 developed, there was plenty of evidence that the economy was going awry and MT’s relations with her powerful Chancellor, Nigel Lawson, already strained, deteriorated badly, with shattering semi-public arguments over policy towards sterling. Over the summer the trade deficit widened to record levels and interest rates began to rise to cool the economy.

The files released here contain little about the fundamentals of economic policy, but there are a number of documents showing the depth of antagonism that sadly came to exist between Chancellor and Prime Minister. Generally No.10 functioned superbly, but it is possible some of MT's officials and advisers were occasionally and unhelpfully inclined to wind her up a bit where Lawson was concerned.

For example, at a point of high tension over sterling did one of her Private Secretaries (not even one with responsibilities in the economics area) have to send her a leading article in the Sun aggressively laying into the Chancellor, and the Foreign Secretary, for good measure? “There can rarely have been a more shameful act of disloyalty and ingratitude than that just shown over the pound” [by Lawson and Howe]. Lawson’s “sulks make Ted Heath look like cheerful Charlie Chester”, and so on. Lawson's memoirs record his strong impression that Bernard Ingham's daily press digests, which he saw from time to time, often worked to similar effect. Whether this was true or not, one can say that some in the No.10 machine well understood the danger to the government from divisions between No.10 and No.11. Briefing MT for an interview with the Wall Street Journal in Jan 1988 Paul Gray (the Private Secretary actually responsible for economics) put the risk of wedge-driving to the fore. In this context it is worth noting that MT did not always get warm support from Conservative backbenchers during her disputes with Lawson, as evident from notes of her meeting with the 1922 Executive in June, the very people who were worried in January about the lack of decent opposition.

An encouraging comment reached MT from an unexpected source in the Commons at the height of her public divisions with Lawson, in mid-May, when there were especially sharp clashes across the despatch box at PMQs. Her PPS, Archie Hamilton, reported to her a private remark about Neil Kinnock made to him by Dennis Skinner, the left-wing Labour MP for Bolsover whom Lawson rated highly for his shrewdness on economic questions. Skinner said of his own leader: "She hit him for bloody six all this week. He's not up to it".

Ingham’s press digests are the best source in these files for the public rowing between MT and Lawson, straddling the budget and running into the summer (page after page is devoted to MT-Lawson stories). Lawson’s memoirs record that he would have liked to leave office that summer, and in fact it was an open secret at the time that he was looking for a new job, discussed for example in Woodrow Wyatt’s diaries. Would he become something in the City, or editor of The Times? These public disputes with MT made it far harder for him to make that exit, and the timing of the July reshuffle (a reshuffle before rather than after the summer recess, as was MT’s usual practice) narrowed his options further. Then over the summer, bad trade figures hammered in the final nail. Resignation after that would have looked like running away. The last chance of a remotely amicable departure had passed.

There was perhaps one small sign in the reshuffle that MT was looking to ease relations with Lawson: she promoted Archie Hamilton to a job at the Ministry of Defence, replacing him with someone who was close to the Chancellor - the Treasury whip, who had also previously been his PPS, Mark Lennox-Boyd. We have Lawson’s letter of congratultions to Lennox-Boyd, ending: “Do let us have a chat over a drink before too long”. Conceivably Lennox-Boyd might have played the kind of role smoothing relations between PM and Chancellor that her old PPS, Ian Gow, did in her first term - he and Geoffrey Howe were good friends, fellow Wykehamists. Another significant olive branch that year was MT’s decision to give Lawson the use of Dorneywood in succession to Whitelaw, who resigned in Jan 1988. She broke the good news at a quiet supper at No.11 on a Sunday evening later that month where Lawson shared with her his thoughts on the coming budget.

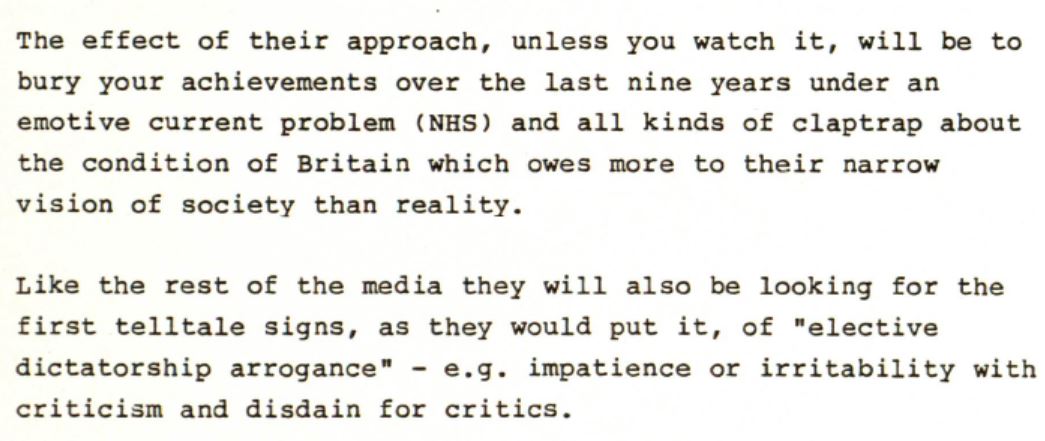

Economic difficulties were unwelcome in any number of ways. Peter Brooke pointed to this in his shrewd strategy paper in August, which MT marked “very helpful”: “our record on the economy underpins our political strength. It is because we are competent in dealing with economic matters that we are considered competent to tackle other tasks”. Quite apart from the direct hit to perceptions of competence, economic problems threatened what had become a staple Conservative argument: the claim that just about every area of policy required the spending of money, which in turn required the economy to perform, which in turn (the argument went) required a Conservative Government. Ingham reflected as much in his briefing for MT before the Dimbleby interview at which she announced the NHS review in late January.

Whatever the warning signs, actual economic pain lay in the future, however. During 1988 measures of economic well-being were high and there were some good moments in the Thatcher-Lawson relationship too. The budget was the most notable of these, reducing the basic rate from 27 to 25p and the top rate of income tax from 60 to 40 per cent. MT described it to friends as having “something for everyone”, as an “exciting” budget, and received a congratulatory telegram afterwards from someone not particularly known for her economic expertise but who stood to benefit mightily from a cut in the top rate – romantic novelist Barbara Cartland: “So thrilled as this is the first time in years that we have not been the sick man of Europe”. Lawson was one of Britain’s most effective Chancellors, and this was the budget by which he will be most remembered, one of the most enduring and significant reforms of the tax system in British fiscal history. One might almost call it the high water mark of Thatcherism. The budget was not especially well received by the public though. Perhaps the most striking document in the files is polling that showed the top rate tax cut was thought deeply unfair (61:33). Indeed the budget as a whole received the worst reception in polling terms on the fairness issue than any since the nadir of 1981, only 28 per cent seeing it as fair, and even among Conservatives the figure was no higher than 54 per cent. That said, more people thought the budget would make them better off than not (43:40) and some elements were warmly supported, such as the introduction of independent taxation for husband and wife.